Multiple Layers of Caching

August 27, 2018 · Filed in ArchitectureCaching is one of my favorite topics in technology. I’ve been fortunate enough to approach this problem from both a hardware and software perspective. This blog post will cover some of the basics of caching, yet focus on the importance of having multiple layers of caching in a system. I think this is a key point worth emphasizing as I’ve seen it commonly misunderstood.

A caching anecdote

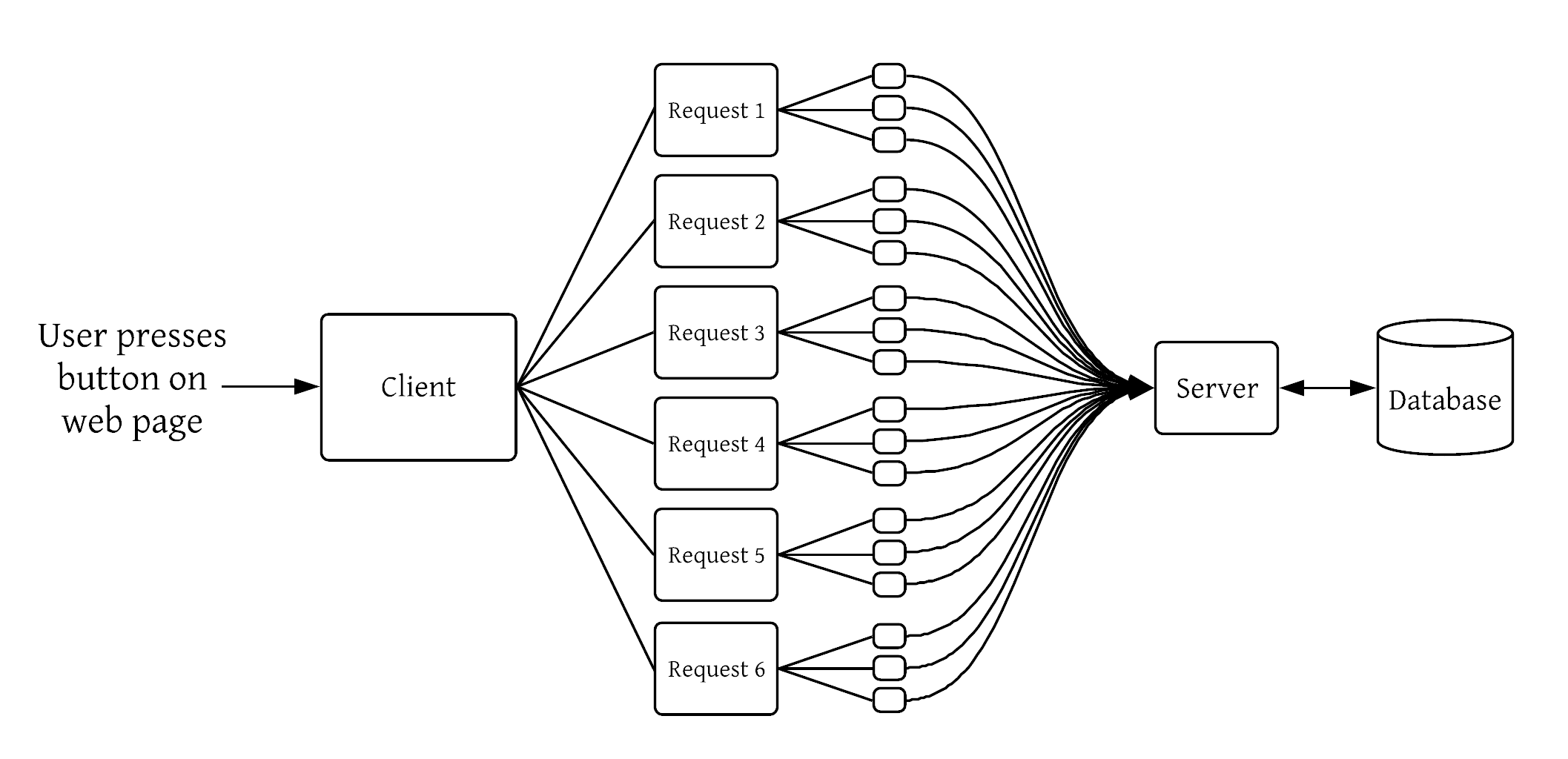

One of the systems I built at Qualtrics could be described as the “back of the backend” as it was a critical storage system that many services relied on, yet had no service dependencies itself. In this position, it was subject to any and all misuse by its consumers. It suffered from what I grew to call the multiplier effect, a condition where a single request (perhaps from a user clicking a button in a UI) caused a few hundred requests and for each one of those requests, issued several more requests, and so on, leading to potentially thousands of requests making it to the back of the backend. I recall determining that the cause of 17,000 requests to my service within a few minutes was caused by the click of an Export button.

Let’s talk about those 17,000 requests some more. If each request was unique and necessary for the result to be produced, then so be it. We should scale our services to handle the load. Maybe throw in some rate limiting so we can throttle the traffic at the cost of increased latency. As you can probably guess in the context of a blog post on caching, however, these 17,000 requests were for a mere handful of objects that rarely change!

While our service handled the request load adequately in this case, my team became motivated to start tracking down obviously bad patterns like this to see what we could do to help our consumers utilize our service more efficiently. It was in this process that I came to understand a core principle: performant systems require multiple layers of caching with participation from both clients and servers.

Reasons consumers chose not to cache

In talking to consumers about why they were not caching, we heard several reasons:

- Our service is just a stateless worker processing a job queue

- There isn’t any way for us to know when we should invalidate our cache

- The backend already has a few layers of caching, so it’s unnecessary

Let’s talk through each of these cases and see if we can come up with a way to still introduce caching.

Stateless worker

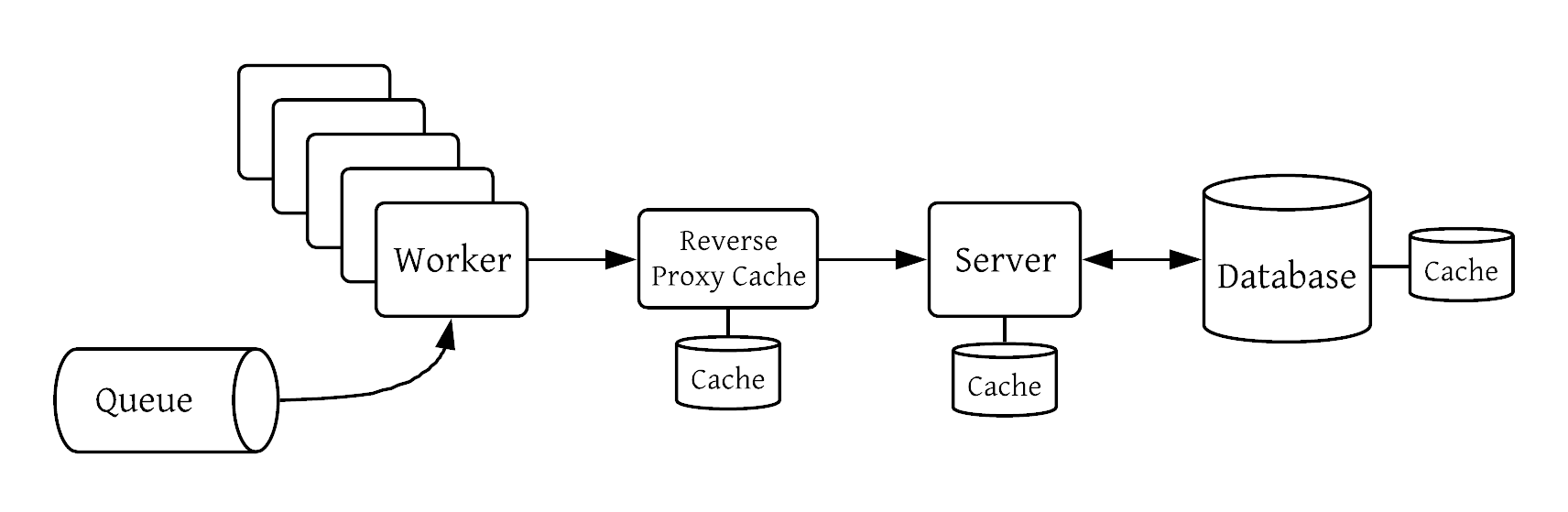

Example scenario: the client is pulling jobs off of a queue, doing some work, making requests to external services, and moving onto the next job. Each job starts with an allotted amount of memory and can’t reasonably cache things in that space.

Potential solution: make requests through a reverse proxy cache. This is a proxy layer with a cache that represents an external API. When a request is received, it determines whether a cached response is ready; if not, it makes the request to the external API and caches it for later. Not all requests will be cacheable, so this service acts as a best-effort caching layer that reserves the right to fall back on the “origin” external service.

Invalidation concerns

It’s fair to be concerned about invalidation: you are just a consumer making it challenging to know when the data changes and therefore should be invalidated.

Potential solution: configure your cache to expire after a given amount of time, known as TTL (time to live). If the cached data rarely changes, risk a long TTL. If consistency is of utmost importance and data changes regularly, have a short TTL.

Consider an example API that returns a time value. If the value is years, it’s obviously highly cacheable. If it’s milliseconds, it’s not very cacheable. But even in the millisecond case, a short TTL cache could still make sense to give several requests a “snapshot” of the data. Requests made to populate a single web page have this quality: would you rather make a slew of requests against a consistent view of the data, or make half of the requests against a different version of the underlying data because it changed mid-load? The consistent view makes a lot of sense for most use cases, making a short (maybe 5-20 seconds) TTL cache very attractive.

Redundant caching

The argument that “the server is caching, so why should the client?” is very common in my experience. Perhaps it’s because we’re taught as developers to avoid duplication (Don’t Repeat Yourself1). One might argue that several teams implementing caching is a form of wasteful duplication of effort. While multiple layers of caching can introduce complexity to a system, it’s not wasteful and not even true duplication because client-side and server-side caching are potentially very different.

Memory hierarchy

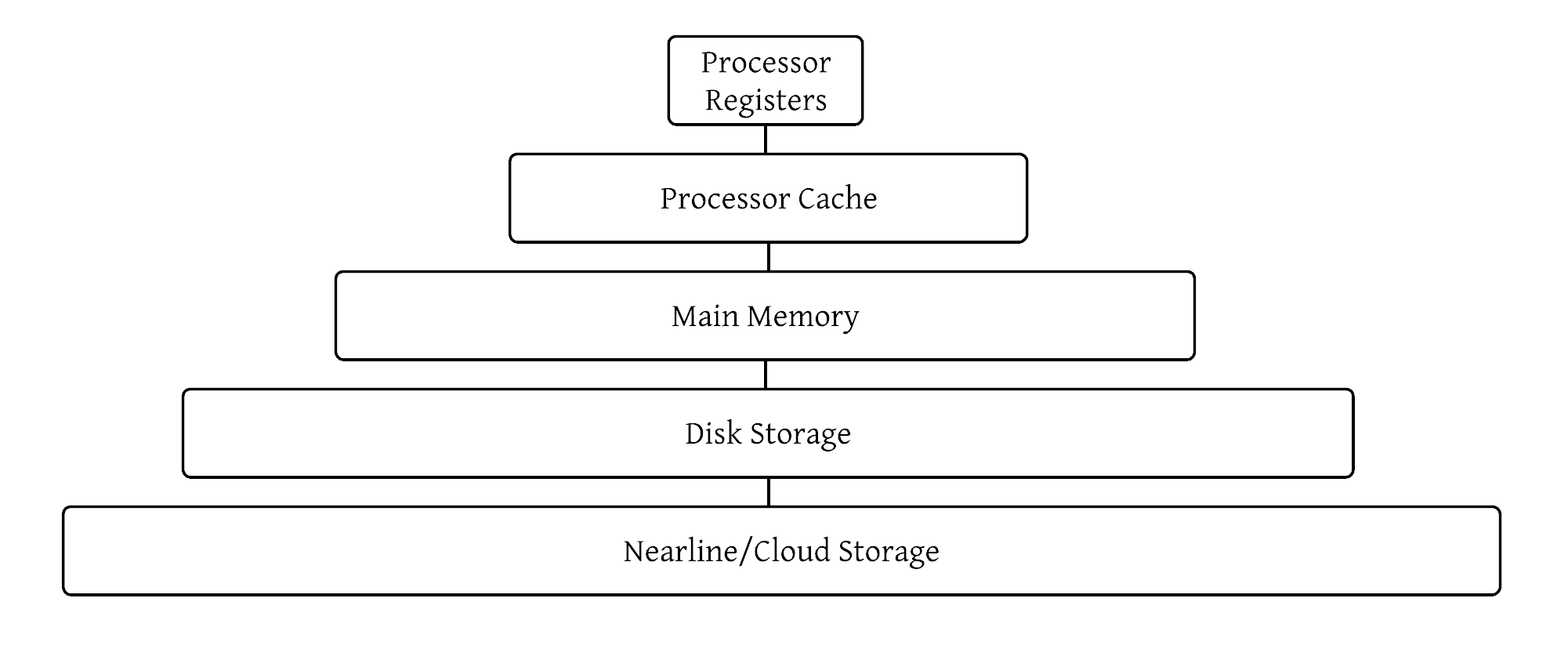

My first in-depth introduction to the concept of caching was in the context of hardware in a Computer Architecture class. In this class, I learned about the fascinating topic of the memory hierarchy2 which I think has some striking parallels to caching in a distributed system.

The memory hierarchy organizes the various forms of computer storage (CPU caches, RAM, disks) according to response time. The registers in a processor are the fastest possible, usually requiring only a single CPU cycle to retrieve their contents. Next is the processor cache which itself has multiple levels (L0, L1, and so on). Access speed for L1 data cache is around 700 GB/s. Next in the hierarchy is main memory (RAM) with speeds of 10 GB/s. Then comes disk storage at 2000 MB/s. The bottom of the hierarchy varies depending on use case, but could be a cloud-based storage system or nearline storage which allows exabytes of data at an access speed of 160 MB/s.

Each storage system in the hierarchy can be thought of as a caching layer. Just like a computer system would be terribly slow and unusable without RAM, a distributed system without some layers of caching would likewise not perform optimally. What we’re seeing here is the benefit of data locality. A RAM cache is much faster than a disk-based cache, but cache memory is much faster than a RAM cache because it’s so close to the CPU! When we can get data close to the system that’s processing it, our throughput increases dramatically.

A key property of the memory hierarchy is that one of the main ways to increase system performance is to “minimize how far down the [hierarchy] one has to go to manipulate data.”2 The same is true of a request as it flows through a system: if the data is cached in a client-side application, it doesn’t have to make network hops to a backend system, wait for a database query to run, and propagate the response back up.

The power of client-side caching

In general, clients have a better sense than the server about workflows that could be aided by caching. As a defensive mechanism, the backend can try to identify highly-requested objects and cache them. While this is helpful, it’s a reactive strategy. The client can proactively cache an object that it is likely to request a lot, saving network calls and bandwidth.

Clients can also set a more accurate TTL for the cache. A backend server with a defensive cache might set a relatively short TTL to ensure that the data doesn’t go stale–servers must respond to the varied needs of many clients, so they have to make safe decisions. On the other hand, one particular client may not be sensitive to stale data, so they set their cache’s TTL to an hour.

Metadata and Navigation

Subscribe

Subscribe via my newsletter or RSS feed